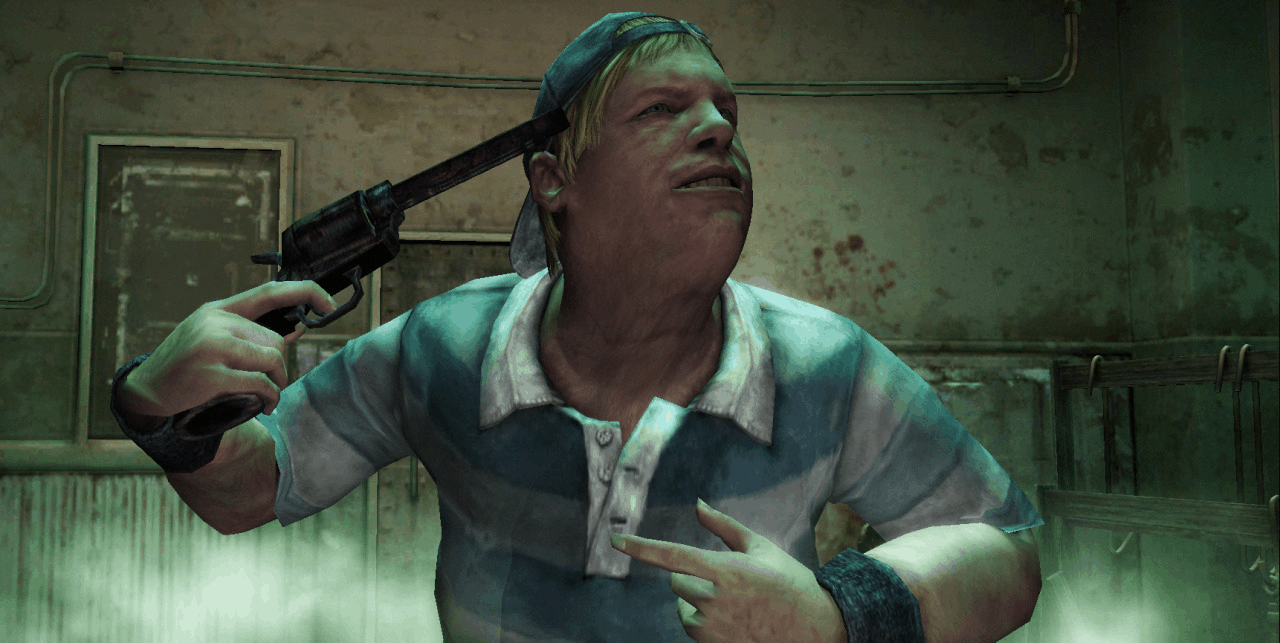

While exploring the town, he meets teenage runaway Angela, an angry young man called Eddie, an eight-year old girl called Laura, and Maria, a woman who looks nearly identical to his ex-wife but with a more flirtatious, confident attitude. He quickly discovers though that he’s not the only person who’s come to Silent Hill seeking answers. But when James gets there, he discovers that what was formerly a tranquil, idyllic tourist trap has transformed: now covered by thick fog, the town is shuttered, decrepit and largely abandoned, except for the hideous misshapen beasts roaming the streets. Except that as Silent Hill 2 opens, James abruptly receives a letter from his supposedly deceased wife, urging him to meet her in their ‘special place’ in the north-eastern US town of Silent Hill. You play as James Sunderland, a middle-aged man struggling with depression and grief following the death of his wife Mary from illness three years previously. And it does it so while simultaneously managing to be consistently, relentlessly terrifying. Not only does it remain the series’ high water mark, it also stands, to this day, as a testament to what video game storytelling can achieve. The same cannot be said of 2001’s Silent Hill 2, which acts as something of a standalone title with a narrative that differs significantly from the other games in the series. What you saw was largely what you got, no matter how hideous or disturbing it was. There were no real layers to the evils on display, no ambiguity or room for interpretation.

But though both games inspired genuine dread, with the first Silent Hill in particular helping to revolutionise survival horror gaming, story-wise they were relatively conventional, with fairly straightforward plots centring on cult rituals and demonic summoning. But for a while in the late 90s and early 2000s that’s exactly what Konami’s Silent Hill series did. Set in the mysterious titular town, both Silent Hill 1 and 3 offered up nightmarish visions of supernatural evil. It takes a lot to really get under someone’s skin and stay there.

Nonetheless, real fear – complex, deep-rooted, long-lasting terror – is something that few games fully achieve. The Resident Evil games and movies might both share a taste for campy dialogue, B-movie thrills, and action set-pieces, but only the games are ever truly frightening.

In a weird way, those horrors onscreen are happening to you, and this often gets the heart pumping and the pulse racing in a way that watching a film as a passive observer just doesn’t manage. After all, the player’s on-screen avatar is, in a way, an extension of themselves in a way that a movie character is not – you control them, you make their choices. The immediacy of video games as a medium in many ways lends itself to horror.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)